-

Traffic

Get More Traffic

SponsoredLinX offers a number of different services to help drive more qualified traffic to your website. Google Ads Management Search Engine Optimisation Microsoft Ads Facebook Advertising Google Ads Mobile“SponsoredLinX are a rarity in today’s market place, they promise a lot but deliver more. Our business has grown by over 400% in one month; we are amazed at the difference they have made.”

-

Conversion

Convert More Leads

Our second step is making sure that your website is able to convert the traffic you receive into leads for your business. Optimising your website to convert more leads is important to a profitable campaign. Web Development Convertopages Do It For Me eCommerce“I just want to say thank you! The changes that you have applied in our AdWords campaign have definitely seen an improvement on click quality and sales for HippityHop.”

-

Retention

Retain Your Customers

As you build up a customer base you need to make sure to keep engaged and retain your relationship. LinX App“SponsoredLinX fully redesigned our main company website with a fresh, clean and professional look. The ‘Google friendly’ web design were part of the fantastic ongoing service we received.”

For Better or Worse – The Right to be Forgotten

Censorship or your privacy?

While the rest of the world, particularly the West, have concrete ideas as to which side of the fence they stand on; the right to privacy vs. the right to freedom of speech, Australia seems to still very much be sitting on the fence. Is a consensus needed, and if so, when will it eventuate?

While the rest of the world, particularly the West, have concrete ideas as to which side of the fence they stand on; the right to privacy vs. the right to freedom of speech, Australia seems to still very much be sitting on the fence. Is a consensus needed, and if so, when will it eventuate?

Sifting through all of the information currently circulating about the ‘right to be forgotten’ and the arguments which stand against it is time-consuming to say the least. Here we have collated what each side of the debate is arguing to try and shed some light on the situation.

The right to be forgotten

Key points on this side of the debate refer to the fact that the original content is not what is being taken down. Links are only being removed from particular domain names such as Google.fr or Google.de (France & Germany) for example. The links are not being taken down from Google.com

Say someone wants to find a report from the BBC, but cannot find it on Google.de, for example. All they have to do is either switch to Google.com, or, search the BBC site itself. This has become a point of contention as the EU privacy regulatory group claims that this practice doesn’t do enough for the ‘right to be forgotten’. The court guidelines provided from the ruling though only applies to people residing within the EU and not overseas, therefore giving no jurisdiction over content links from a domain name such as Google.com (Scott, 2014).

In response to claims that the right to be forgotten goes against the right to freedom of speech, privacy regulators from the 28 European Union member states state that the content is still on the internet, individuals are not requesting that the original content be taken off the internet. What they are asking to be taken down are Google’s links to the content (Scott, 2014 & Essers, 2014).

The right to be forgotten is particularly appealing to victims of “… revenge porn, where intimate images are published by disgruntled ex-partners or hackers…” (Stilgherrian 2014), and perhaps victims of internet trolling, or people and/or businesses which have been subject to false and misleading reviews from competitors. Even links to long-forgotten legal disputes which no longer hold any relevance in modern day-to-day society can be requested to be taken down.

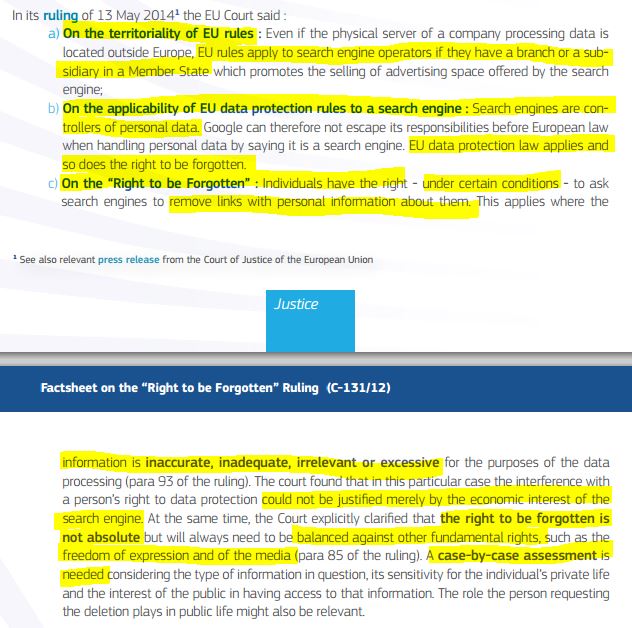

*Source: Factsheet on the “Right to be Forgotten” ruling (C-131/12)

The right to free speech

There is an argument on this side of the debate which is that there is a fundamental difference between companies voluntarily giving the public the opportunity to request links to be taken down, in comparison to a court ruling which now deems the request, a.k.a. the right to be forgotten, as backed by the state, to immediately bring issues of censorship to the surface, like an angry ancient monster disturbed from its depths (Breheny, 2014).

In the image above you can see in bold and highlighted in yellow, “… inaccurate, inadequate, irrelevant or excessive…”, but the trouble is that one person’s idea of ‘irrelevant’, or ‘excessive’, for example, could be substantially different from someone else’s idea.

Civil Liberties Australia vice president Tim Vines was quoted as saying in an article written by Henry Belot that, “… there was little guidance for companies on how to weigh the competing values of freedom of speech and expression of privacy, and there was a risk that the process will lack transparency and consistency”.

The key is that the right to privacy and the right to freedom of speech are two different things and need to be seen as such. On top of this, if there are changes in laws, it will come down to the minutest detail and how they will be enforced; it must be a level playing field for all. The vague language which has been used in the court document from the Court of Justice of the European Union has created much confusion and any future documents need to provide detailed and specific guidelines. But for now, it seems that Australia will have to get comfy sitting on that fence for a little while longer. The question is, will the ‘right to be forgotten’ become the introduction to modern censorship which we all fear occurring, or will it mean that individuals can finally be in control of their own personal data?